Happy Birthday, Stanford White

The Early Years

Lifelong New Yorker. Brilliant architect. Society man. Philanderer. Victim.

Birthday boy.

From the moment he was born on November 9th, 1853 to Richard Grant White and Alexina Black Mease, Stanford White lived a charmed life. While his parents had no money, they were rich in other ways. Richard White was a Shakespearean scholar who spent his days rubbing elbows with the city’s artist elite. Stanford grew up in a home on East 10th street surrounded by the likes of John LaFarge, Louis Comfort Tiffany, and even Frederick Law Olmsted.

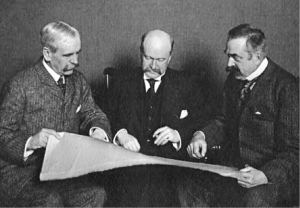

Stanford’s connections served him well, and at 18 years old he secured a position as the principal assistant to one of the greatest American architects of the day: Henry Hobson Richardson. This illustrious beginning gave White the cachet and skills he needed to embark on his own, and by 1879 at the ripe old age of 26, joined the now famous McKim, Mead, and White firm that would transform the face of growing New York.

Together, these three men painted the town Beaux-Arts. Inspired by classical Greek and Roman styles, you can find many examples of their work still around the City today. White’s own estate Box Hill—where his wife Bessie resided—was a showplace to illustrate the design aesthetic the firm was peddling. Just look at The Morgan Library and Museum, the Manhattan Municipal Building, Bellevue Hospital, Prospect Park, or Judson Memorial Church and you’ll see their distinct style. And while the three men agreed that all designs would be considered the product of the collective firm and not one individual architect, there’s one particular work that stands apart. A passion project that White alone takes credit for: the Arch in Washington Square Park.

The Arch

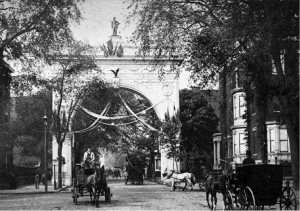

In 1889, New York City was preparing for a three-day extravaganza to commemorate the Centennial anniversary of George Washington’s inauguration at Federal Hall on Wall Street. Determined to insure that the celebrations reached Washington Square Park, Greenwich Villager William Rhinelander Stewart conceived of an attraction; a triumphal Arch that would stretch across Fifth Avenue.

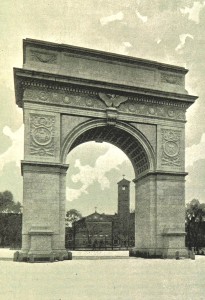

Modeled after the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, made of wood and plaster and painted ivory, the original wooden Arch was so spectacular that the entire Centennial Parade route was shifted to pass under the monument. Festooned with flags and topped with an early wooden statue of George Washington, the Arch was such a sensation that by the close of the celebrations, neighborhood residents were already clamoring for the Arch to remain. When a few days later White was asked to design a permanent monument, he was so enthusiastic about the idea that he took the project on project pro bono.

White pulled out all the stops for his design, taking a modern interpretation of classical form. Allegorical figures, laurel wreaths, and bands of decorative motifs—sculpted by Frederick MacMonnies from White’s design—adorn the Tuckahoe marble. Angel figures (intended to look like Mrs. White and Mrs. Stewart…with limited success) carry banners and horns, symbols of war and peace. 14 carefully carved “W’s” march around the top of the Arch. A sword wrapped with a wreath of oak symbolizes war and nearby laurel wreaths represent victory. But despite this level of detail, the overall shape of the Arch is still less bulky and intricate than its lofty predecessors, a testament to White’s modern eye.

Personal Life

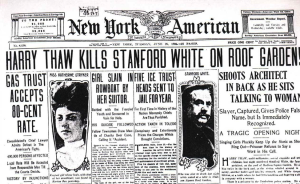

While White is often remembered for the beauty he created, the end to his story is ugly and dark. In 1901, the 47-year old Stanford White began an affair with a 16-year old model and showgirl named Evelyn Nesbit. For a year the two were engaged in an odd “relationship,” an affair that continued even after White assaulted a heavily intoxicated Evelyn one evening in an attack that would be considered rape by today’s standards. Eventually the two separated. White moved onto others and Evelyn moved onto marriage, tying the knot in 1905 with a man named Harry Kendall Thaw; a millionaire…and a mentally unstable drug addict.

Not-so-coincidentally, Thaw had been obsessed with White for years, convinced that the well-connected man had been shunning Thaw from New York society. And his hatred for White only grew after discovering the truth of Evelyn’s assault. Not that Thaw was one to judge, since he himself beat and raped Evelyn Nesbit during a trip the two took to Europe before their marriage.

On June 25, 1906, Thaw finally gave in to the hatred in his heart. During a musical performance at the outdoor rooftop theater at the original Madison Square Garden (which was designed by McKim, Mead and White), Harry Thaw snuck up behind White, and shot him three times with a revolver. White was hit once in the shoulder and twice in the head, and was killed instantly. Thaw didn’t even try to run, he simply put his hands over his head and announced to anyone not too busy running away to listen, “I did it because he ruined my wife! He had it coming to him. He took advantage of the girl then deserted her.”

Harry Thaw’s trial was dubbed “The Trial of the Century” by papers at the time. Evelyn shared details of her relationship with White that scandalized the city. Thaw was found not guilty on the grounds of insanity at the time of the murder and sentenced to involuntary commitment for life, but he escaped from prison and fled to Canada. Despite this theatrical turn of events, Thaw was eventually judged sane, cleared of his charges, and allowed to go free.

Stanford White led a memorable life. It’s easy to remember him fondly for the beauty he brought to the city, and to Washington Square Park. But his flaws cannot be ignored in favor of his gifts. On his birthday we reflect back over the good and the bad, the beautiful and the ugly, the reality of the man who helped beautify this city.