The Original Park People

Each November, we take time to recognize Native American Heritage Month. You may not realize it, but when you spend time in Washington Square Park, you’re surrounded by native history. Join us as we explore some of that history and learn about the Indigenous people that lived their lives in and around the land we now call Washington Square Park: the Lenape.

Long before pavement and parterres, Washington Square Park was wild. It was a lush marshland teeming with plant and animal life, an idyllic spot on the island known as Manahatta, or land of many hills, to the Lenape. The land actually had a similar purpose to how we use it now. It was a gathering place and cultural hub where Lenape would come to trade and play games or music. Starting west and running south of where the Arch now stands flowed one of the largest natural watercourses in Manhattan, Minetta Creek. Minetta may have come from the word Manette meaning Devil’s Water. Although the creek was buried in the 19th century, it still resonates as part of Greenwich Village history. In fact, Minetta Street was built following the curvature of the creek’s original path.

The Lenape live all over the Northeastern Woodlands, what we would today call Canada, New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania along the Delaware River watershed, New York City, western Long Island, and the Lower Hudson Valley. Often they can be confused for a single tribe, but the reality is much more complex. The Lenape people are comprised of smaller tribes who speak similar languages and share familial ties. Some Lenape speak Unami while others speak Munsee. Although all Lenape belong to the same group, a Lenape citizen would identify first with immediate family, clan and village, then neighboring villages, and finally through language with more distant communities.

For the Lenape who lived in this area, the lower part of the island would have been one of a number of seasonal camps that they migrated among during the year. What we now call Greenwich Village is known as Sappokanican to the Lenape. This roughly translates to the “land of tobacco growth,” which makes sense given the importance of farming for the Lenape. Although the European idea of private land ownership was alien to the Lenape, they did care for and work the land. It belonged to the families within the clan collectively while it was inhabited.

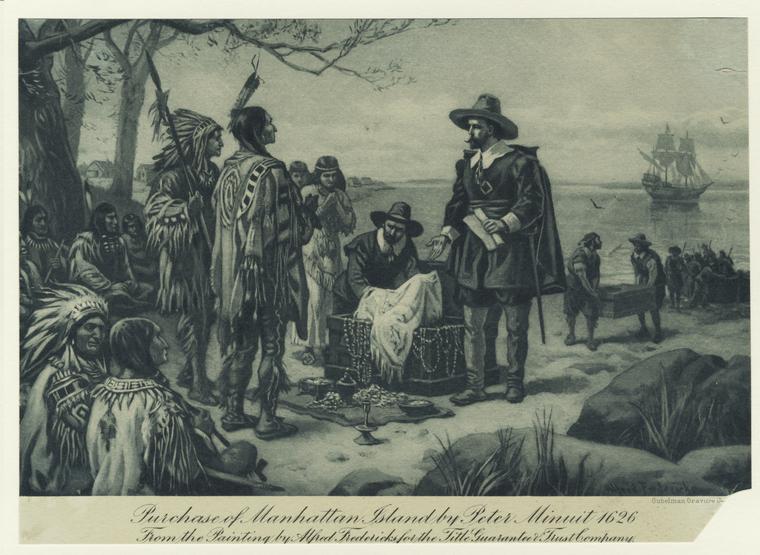

As is the story with all Native American tribes, their way of life was irrevocably altered by the arrival of European settlers. When the Dutch first arrived in Lower Manhattan in 1624, relations were peaceful. But the peace was not to last. In a now infamous—and somewhat questionable—story, the Lenape “sold” Manhattan to Peter Minuit, Director of the settlement, for 60 guilders, or about $24 at the time. This pitiful price might raise a few eyebrows, but remember, the Lenape don’t conceive of land “ownership” the way the Dutch did. They likely wouldn’t have seen the transaction as handing over the land, but instead were graciously allowing the Dutch to share the space together. It must have been a rude awakening when they realized the Dutch felt they had complete control over the land that had once been available for all to use.

While there is no historical evidence to prove that the Lenape ever so much as sat down with Peter Minuit, we do know that the Dutch took ownership of the land, sale or no. Conflicts between the Lenape and the Dutch increased as settlers laid claim to the land and the Lenape struggled to maintain their home. And if violent skirmishes weren’t enough, Lenape were killed in droves by diseases carried over from the old world. Even the English ascension to power in 1664 offered no respite for the Lenape. By the early 1700s, the few hundred who managed to survive the European invasion were forced to leave Manhattan. And despite the horrors inflicted upon them, Indigenous people (including the Lenape), have never truly disappeared from Lenapehoking, and are very much still here.

It isn’t only during holidays that we should acknowledge the first stewards of the beautiful land we now call Washington Square Park, but it’s certainly a good reminder. Although much has changed since its beginnings as a marsh, we can have respect for where we stand and appreciate the beauty that can be found there still.