Recognizing Juneteenth

Juneteenth. Freedom Day. Emancipation Day.

However you refer to June 19th, this annual holiday commemorating the end of slavery in the United States has been celebrated since the late 1800s, although it is only in recent years that the day has been recognized as a National Holiday. Juneteenth marks the anniversary of Union General Gordon Granger arriving in Galveston, Texas to inform enslaved African-American people that the war had ended and they were free. This announcement was a long time coming—a full two months after Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered in Virginia and more than two and a half years after President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Enforcement of the Proclamation relied on Union troops, which means the announcement only made it as far as the troops did. As Texas was the most remote of the slave states and did not have many Union troops by the end of the Civil War, prior to General Granger’s arrival, enforcement of the Proclamation had been spotty at best.

159 years later, it’s a day that too many let pass by without recognition or awareness. Here in NYC it’s easy to think that slavery is a piece of someone else’s past. But that does a disservice to those, both enslaved and free, that walked the very streets of NYC we trod today, including the ground that is now Washington Square Park.

The Land of the Blacks

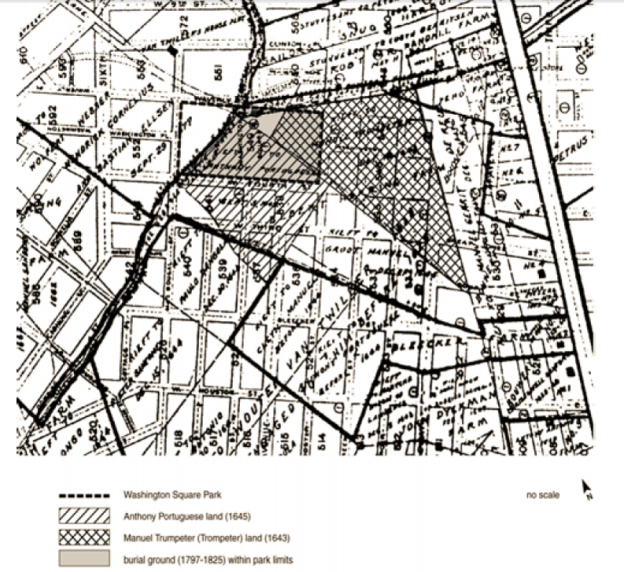

Back when this island was New Amsterdam, the area surrounding what is now Washington Square Park was part of a village settled by people of African descent. From about 1643-1716, this ‘Land of the Blacks’ covered about 130 acres north of the wall of New Amsterdam (where Wall Street is today). About 30 African-owned farms could be found there.

Manuel Trumpeter and Anthony Portugese were just two of the men freed and given land grants, which included parts of what later became Washington Square Park. Despite their freed status and land ownership, these men still lived under conditions we would bristle at today. They were required to give a number of crops and animals from their farmland back to the Colony each year. The West India Company reserved the right to call them into service at any time, although they would be paid for the work. Perhaps most importantly, while men like Trumpeter and Portugese could purchase the freedom of their loved ones, provided they could afford it, their freedom did not automatically extend to their spouses and children.

While these men and women gained a sort-of half-freedom status long before the Emancipation Proclamation or Juneteenth existed, it was nothing close to the real thing. While they did not live to see true freedom, we can remember their lives and their struggles while standing in the same space they once occupied.

To learn more about half-freed slaves in and around Washington Square Park click here.

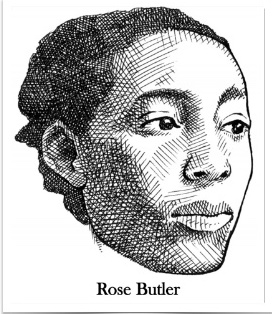

Rose Butler

Even before the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862, New York was recognizing the rights of its African-American population. In 1799 New York passed the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery that declared children born after July 4th, 1799 to enslaved mothers would be born free, with the caveat that they would be required to provide free services for their mother’s masters until they turned 25 (for women) or 28 (for men). It also reclassified existing slaves as indentured servants, who could not be sold but were required to continue their unpaid labor. In March of 1817 New York passed another abolition law to free those born before 1799 under the same conditions of the Gradual Abolition of Slavery act.

Under those statues, 19-year-old Rose Butler should never have been a slave, but for unknown reasons, she was. Born in Mount Pleasant in November 1799, Rose was owned by various households before coming to New York City under the ownership of a man named Abraham Child. In 1817 she was sold to William Morris and his family…and just a year later she was on trial, accused of attempting to burn down the Morris family home while they slept. During the trial, Rose admitted to intentionally causing the fire and tying a string to the kitchen door to prevent the family from escaping. Although there were no reported casualties, and the physical damage was limited to a few kitchen steps, Rose was still convicted of arson and sentenced to death.

On March 5th, 1818, the land that we now call Washington Square Park — then a potter’s field— was witness to its only recorded execution in history. A gallows was erected for Rose’s hanging, which was unusually severe and public in nature. Despite the lack of physical harm to person or property, Rose was still sentenced to death in what was possibly meant to be a show of strength as well a sign to white New Yorkers that they would be “protected” despite emancipation efforts. There are no other recorded executions in the potter’s field to indicate that it was a common practice to hang prisoners there, which is further evidenced by the need to erect a gallows specifically for Rose. Thousands came to watch the execution, which seemed to serve as part warning, part lesson, to the city’s black community. It may have been New York’s complex relationship with slavery at the time that played a role in the harsh treatment Rose received and the apparent efforts to publicize her punishment.

At the time of Rose’s execution, New York was in the throes of a gradual emancipation that began in 1781 when the state legislature voted to free slaves who had fought during the Revolutionary War. By the time Rose was born, the African Free School had been established in NYC to educate both enslaved and free children. By 1790, one in three black New Yorkers was free. Freed, indentured, and enslaved African-America people began to mingle freely in some spaces, including the neighborhood below the potter’s field that would eventually be known as Little Africa. But the progress toward full-freedom was stilted, and the New York legislature took measures that more redefined indentured servitude to allow slavery to continue than took steps towards true emancipation. Slavery was too important to the economic stability of New York City and its agricultural areas.

Following her execution, Rose was likely buried in the potter’s field, so close to the community and freedom she never got in life. Her execution is the only one on record as having taken place in the potter’s field, and it was only a few years later in 1825 that the field was permanently closed. In 1827, just 9 years after Rose’s execution, slavery in New York came to a definitive end—the same year Washington Square opened as a Park. So next time you head to WSP, take a minute to remember those who have come before, and the very different lives so many lived.

To learn more about Rose Butler, click here.

Little Africa

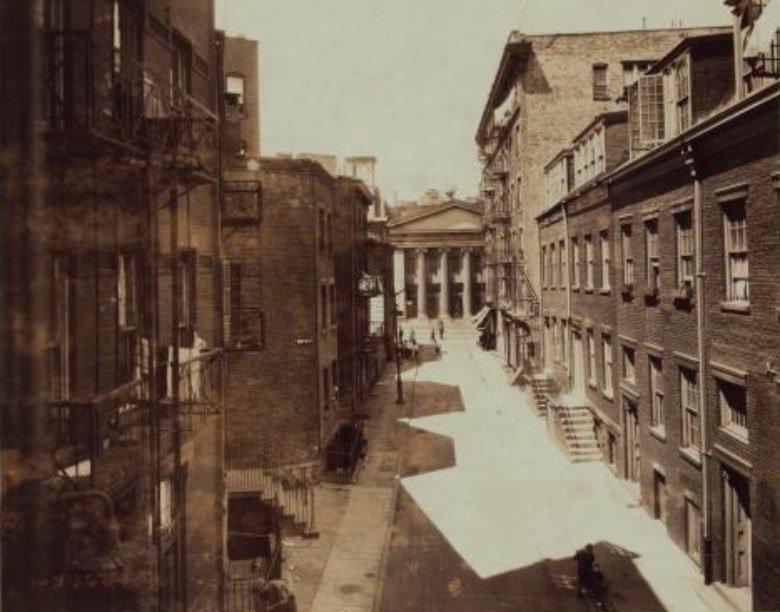

By the mid 1800’s, African-American people from a variety of backgrounds flocked to an ever-developing Greenwich Village. It was a time when urban development was pushing the city further north into formerly more rural areas — like the neighborhood around modern-day Washington Square Park. This created a shift in geographical and social boundaries, and allowed for the development of neighborhoods like “Little Africa,” a rapidly growing free black neighborhood that grew in what had once been farmland tended by half-freed slaves, and is now called Minetta Street. With schools, apartment buildings, and entertainment, Little Africa was a bustling hub of black culture just south of the potter’s field that would one day be Washington Square Park.

To learn more about Little Africa and other black history around the neighborhood, click here.

Countless African-American people have spent time in and around the land that we now call Washington Square Park. Some of them were free, some of them were enslaved, and some of them fell in a hazy middle ground that still used and abused African-American people in this city. While their stories may not be part of the usual Juneteenth narrative, we hope that when you spend time in Washington Square Park this weekend you’ll take a moment to think about the black history that surrounds you.