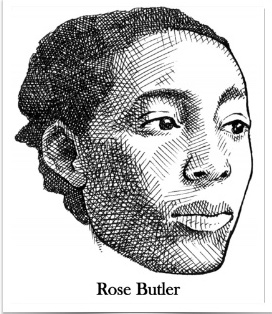

The Life and Death of Rose Butler

It’s Black History Month, and all February long we’ll be exploring different facets of black history in and around Washington Square Park. This week we’re remembering Rose Butler, an enslaved person who was executed in the only recorded public execution in the potter’s field that eventually became WSP.

On March 5th, 1818, the land that we now call Washington Square Park — then a potter’s field— was witness to its only recorded execution in history; that of a 19-year old black woman named Rose Butler.

Rose was born in Mount Pleasant New York in November 1799. And although she was born into a world where emancipation was slowly gaining ground, Rose was still enslaved. She was owned by various households before coming to New York City under the ownership of a man named Abraham Child. In 1817, Rose was sold to William Morris and his family…and just a year later she was on trial, accused of attempting to burn down the Morris family home while they slept. During the trial, Rose admitted to intentionally causing the fire and tying a string to the kitchen door to prevent the family from escaping. Although there were no reported casualties, and the physical damage was limited to a few kitchen steps, Rose was still convicted of arson and sentenced to death.

In a densely packed, highly flammable city like NYC, arson was considered a heinous crime. In fact, the fear of fire was so great that in 1808 New York State had added residential arson to its list of capital crimes. That designation as a capital crime drove Rose’s case all the way to New York’s Supreme Court. There they debated whether Rose’s actions were truly a capital offense worthy of the death penalty, or a common law offense, which commanded a prison sentence. Sadly for Rose, the Supreme Court ruled that her crime constituted first-degree arson, and upheld her death sentence. She was incarcerated for a short time at Bridewell Prison before being brought to the potter’s field for execution by public hanging.

At the time of Rose’s execution, New York was in the throes of a complex period of gradual emancipation that began in 1781 when the state legislature voted to free slaves who had fought during the Revolutionary War. By the time Rose was born, the African Free School had been established in NYC to educate both enslaved and free children, and by 1790, one in three black New Yorkers was free. But the progress toward full-freedom was stilted, hampered by the New York legislature’s measures to redefine indentured servitude in a way that allowed for slavery to continue. Unpaid slave labor was an essential part of the economic stability of New York City and its agricultural areas, and the path to emancipation was long and winding.

In fact, Rose should have never been enslaved in the Morris household. In 1799, New York passed the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery that declared children born after July 4th, 1799 to enslaved mothers would be free. The caveat was that they would be required to work unpaid for their mother’s masters until they turned 25 for women or 28 for men. The law also reclassified those currently enslaved as indentured servants, who could no longer be sold but were still required to continue their unpaid labor for their current master. Rose was born in November 1799, after the law was passed, but her mother’s status is unknown and she may have been one of New York’s free blacks. But even if she was enslaved, Rose should have been an indentured servant, unable to be sold, under her mother’s master. So the sales to Abraham Child and William Morris should never have occurred.

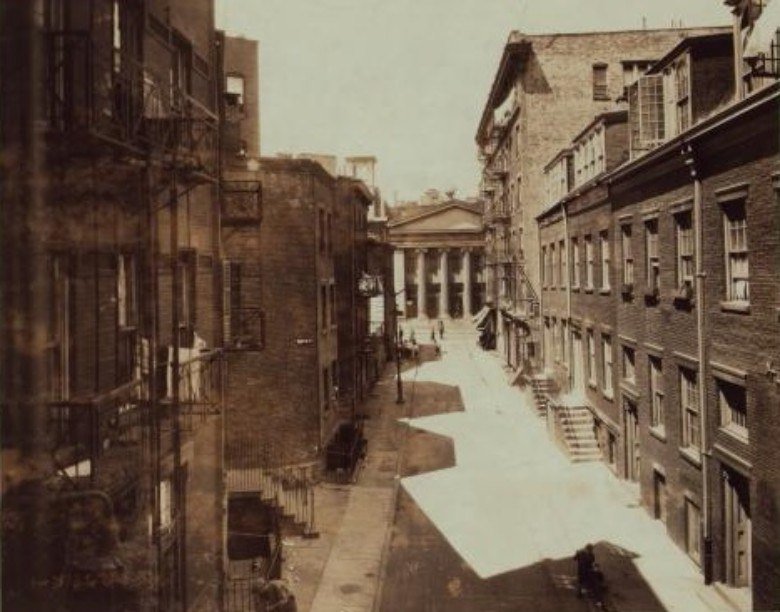

But for whatever reason, Rose was enslaved a stones-throw from freedom, not just legally but physically as well. Just a short walk from the Morris home, free, indentured, and enslaved blacks intermingled in an ever-developing Greenwich Village. It was a time when urban development was pushing the city further north into formerly more rural areas — like the neighborhood around modern-day Washington Square Park. This created a shift in geographical and social boundaries, and allowed for the development of neighborhoods like “Little Africa,” a rapidly growing free black neighborhood centered around what is now Minetta Street, just below the potter’s field. So while Rose’s enslaved status was not necessarily unusual for the time, she would have been surrounded by examples of what free life could be like. It’s unclear whether the lure of freedom is what spurred Rose to action on that fateful evening, but to live so close to something that still seemed far out of reach must have been nearly unbearable.

It seems likely that New York’s complex relationship with slavery played a role in Rose’s brutal treatment, and why her case drew such significant attention. Despite the lack of physical harm to person or property, Rose was still sentenced to death in a public display. This may have been a show of strength, and a sign to white New Yorkers that they would be “protected” despite emancipation. Rose’s execution itself was carried out in an unusually public manner. There are no other recorded executions in the potter’s field to indicate that it was a common practice to hang prisoners there, which is further evidenced by the need to erect a gallows specifically for Rose. Thousands of spectators came to the potter’s field to watch the execution like some kind of gruesome performance. Her execution seemed to serve as part warning, part lesson, to the city’s black community. And perhaps that is why her death still resonates today.

Following her execution, Rose was buried in the potter’s field, so close to the freedom she never got in life. Her execution is the only one recorded has having taken place in the potter’s field (contrary to many myths that have sprung up over the centuries), and it was just a few years later in 1825 that the potter’s field was permanently closed and filled in.

In 1827, just 9 years after Rose’s execution, slavery in New York came to a definitive end. The same year Washington Square opened as a public park. So next time you come Washington Square Park, take a minute to remember those who have come before, and the very different lives so many of them lived.