From Potter’s Field to Parade Ground

January 16, 1826 is a significant date in Washington Square Park’s history. Not because anything particularly grand or exciting happened on that chilly Monday. No. What makes the date important is nothing more than a simple bureaucratic function: the introduction of a resolution.

During newly elected Mayor Philip Hone’s first Common Council meeting on that fateful Monday, Alderman Abraham Valentine introduced a resolution to re-appropriate an old potter’s field into a military parade ground. Up until that moment, the area we now call Washington Square Park served a very different purpose for the city of New York. From 1797 until May of 1825, the land was used as a potter’s field – a public burial ground where poor and indigent people, many victims of yellow fever, were laid to rest. When the potter’s field was first established it was on the city outskirts. By 1823 however, the neighborhood around the field was no longer the sparsely populated suburb that it had been at the beginning of the century. Real estate boomed and new construction sprang up around the field. Shops opened and many new residents made their homes in the area. The city’s population had exploded, growing from about 33,000 in 1790 to 124,000 by 1820. These people needed places to live, which had caused the price of land to skyrocket, but the burial ground was physically too unstable to support commercial or private development. However it could be turned into open land for residents to enjoy.

A pleasant green space had the potential to lure wealthy homeowners and could increase property values (and property taxes) in the surrounding area. Even better, costs for improving the new space could be covered by levying special assessments on neighboring lots that were more appropriate for development.

When Alderman Valentine’s resolution passed six weeks after its introduction, planning began for the new parade ground. It was set to open with much pomp and circumstance on July 4, 1826. Dubbed the Washington Military Parade Ground, the public space was a hit from day one. About 50,000 people attended the Parade Ground’s inauguration jubilee, about ⅓ of the city’s population at the time. And it only took a few months for eight landowners to construct 12 homes on the southwest side of the Park, quickly lending the neighborhood an air of respectability.

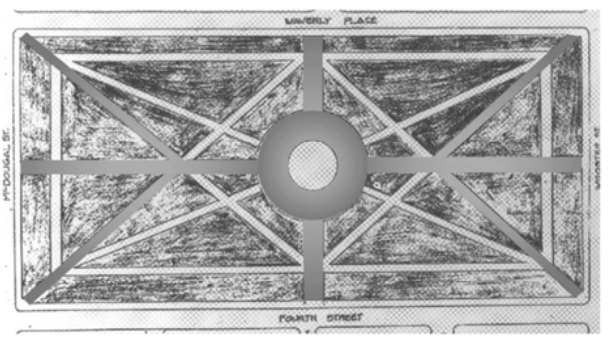

While the borders of the Parade Ground are the same as Washington Square Park’s borders today, the interior looked quite different. The early layout was almost rigidly symmetrical and full of straight lines – appropriate for practicing military reviews and drills. After the Ground officially opened the city spent the next few months levying assessments to pay for greater improvements. While it officially opened as a parade ground – and indeed, volunteer regiments did use it to perform drills – by 1827 it was generally recognized as a public park. And the improvements the city made reflected this shift. New plantings were added and walkways were added to make the area more inviting to residents. The Evening Post (which eventually became The New York Post) described these changes in their May 10, 1828 edition: “Workmen are busily employed putting a handsome fence around this spacious public square…and laborers are busy leveling and preparing the ground to be laid down to green turf with neat gravel foot walks around the margin and across it from each extremity. When this work is completed and proper shade trees and shrubbery are hopefully set out over the whole square, it will afford a most delightful morning promenade.”

Now decidedly looking the part of “Park,” it would still take a few more decades for WSP to gain its iconic monuments. The first fountain was placed in the center of the Park in 1852 (to be replaced by the current fountain in the 1870’s renovation spearheaded by the Commissioner of the newly created NYC Parks Department, William “Boss” Tweed). The Garibaldi and Holley monuments were placed in 1888 and 1890, respectively. And perhaps the most iconic monument, the Arch, didn’t appear on the scene until 1892. But still, even without these familiar features, it was our Park. Which means that even today, when you step inside Washington Square Park’s fence and stroll along the paths or sit on a bench, you’re appreciating the space the same way that New Yorkers have for nearly 200 years.