The Half-Freed Slaves of WSP

It’s Black History Month, and each week we’ll be exploring a different facet of black history in Washington Square Park. This week we’re exploring the history of the half-freed slaves at WSP.

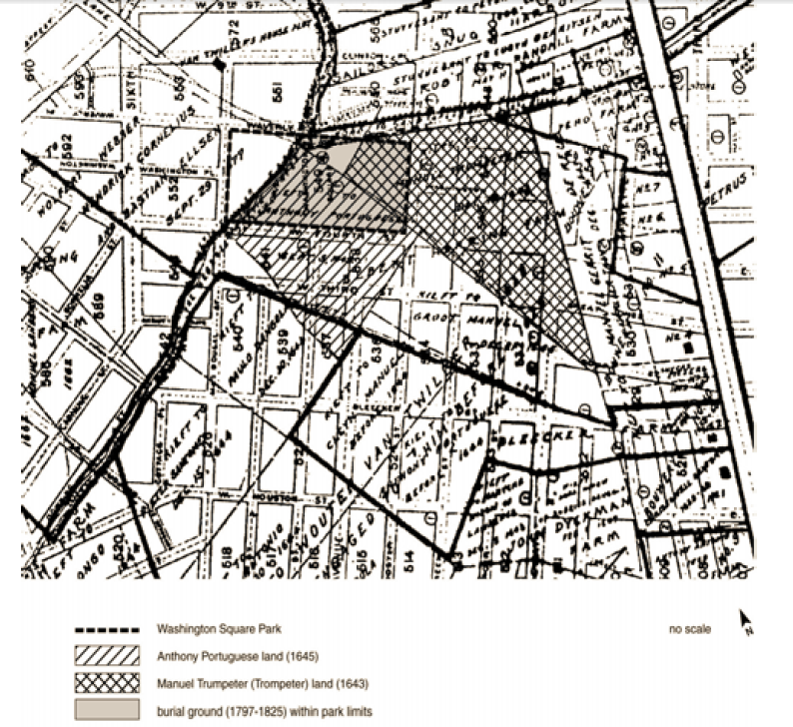

Over 200 years ago, the land that would one day be familiar to us as Washington Square Park was part of New Amsterdam: the Dutch Colony that would eventually grow into New York City. Where you’ll now find daffodils and cherry blossoms blooming were once rolling fields of farmland. But the land wasn’t tended by Dutch colonists or European farmers. It was worked by two men named Anthony Portugese and Manuel Trumpeter; and they were half-freed slaves.

When Manahatta (the Lenape name for the island of Manhattan) was first settled as New Amsterdam in 1626 by the Dutch West India Company, black slaves played a large role in Colony life; the Company itself owned about 70 slaves. However, their circumstances looked significantly different than what usually comes to mind when we think of slavery in the United States. Thanks to records surviving from the colony, city, and church, we’re able to get a glimpse of what their lives would have been like. An article by Peter R. Christoph, The Freedmen of New Amsterdam explores what life was like in the colony under Dutch rule. Anthony Portugese, at one point in 1638 sueda white merchant for injury to his hog. This minor legal squabble is the perfect example of how half-freed slaves of the Company like Portugese differed from the slaves of the United States. He was allowed to own property, and had redress in court, rights that slaves living in British New York would never have had. Along with these rights, slaves in New Amsterdam were permitted to marry, to inherit property, to be baptised, and to be paid for work done outside of Company time. They were even given weapons and asked to help in the Colony’s fight against the natives.

In the early and mid-1640s, Willem Kieft, the fifth Director of New Netherland and Director of the West India Company, began granting freedom to Company slaves. These men were given plots of land to farm, enough to feed themselves and their families. Manuel Trumpeter and Anthony Portugese were just two of the men freed and given land, and their grants included parts of what later became Washington Square Park.

Despite their freed status and land ownership, however, these men were still slaves. The designation “half-free,” is because their freedom was not absolute.. They were required to give a number of crops and animals from their farmland back to the Colony each year. The West India Company reserved the right to call them into service at any time, although they would be paid for the work. Perhaps most importantly, while men like Trumpeter and Portugese could purchase the freedom of their loved ones, provided they could afford it, their freedom did not automatically extend to their spouses and children. While these stipulations carried on after Kieft, before the English took over in 1664, Peter Stuyvesant, the last Director of the Colony, freed all remaining Company slaves.

While we have historical documents to give us a glimpse at life back then, they do not provide the thought processes behind the decisions the Company made regarding its slaves. The Colony’s food needs likely played a large role in the decision to disburse land grants, as at this time it was a Company town dominated by fur trade, not farmers. It may have also been a way to keep laborers docile and happy. Safety may have also been a factor. In the 1600s, the main part of the city was growing at the tip of Manhattan, which put the land grants pretty far on the outskirts of town. They would have provided a buffer between the hostile natives and the Colony proper.

We will never have a complete picture of what the lives of Trumpeter, Portugese, and the other men like them truly were. But these glimpses into the past do show us that there is plenty to ruminate on as we imagine what life was like for Trumpeter and Portuguese, who farmed the land on what is now Washington Square Park.