From Wild to Designed: The Landscape of Washington Square Park

For so many of us, Washington Square Park is the place we go to connect with nature. But make no mistake, this space, as lush and thriving as it may be, is not natural. This is a built space, constructed with your enjoyment in mind. Intentional infrastructure threads itself between the lawns and the garden bed and through the iconic hex pavers under your feet. You are surrounded by deliberate choices that have shaped this land in big and small ways over the course of a few hundred years, multiple uses, and a handful of renovations. Follow along with us as we explore the changes that have literally shaped the Park from wild marshland into the public space we love today.

Before Dutch settlers arrived in “Mannahatta”, the land of WSP was wild marshland. The Lenape would have fished and hunted here, along the banks of a creek we now know as “Minetta.”

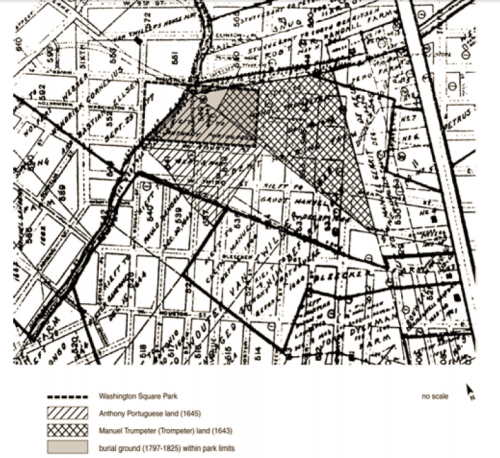

Once the Dutch arrived and began taking over, the land became less wild. In an attempt to buffer the city proper from border wars with the Lenape, the Dutch gave half-freed slaves land grants to farm. We refer to these individuals as “half-freed” because while they had their freedom, their children did not and remained property of the Dutch West India Company. The farms of two men, Anthony Portugese and Manuel Trumpeter, encompassed the land that is now Washington Square Park. Long before its use as a public park, the area is modified to serve a specific human purpose.

When the English take over New Amsterdam in 1664, the area remained farmland, and was essentially a suburb of the city proper, which sat at the tip of the island through the 1780s and 90s. A series of wealthy landowners farm here, creating country estates for New York’s elite to escape to. And as the neighborhood begins to develop, so does the land.

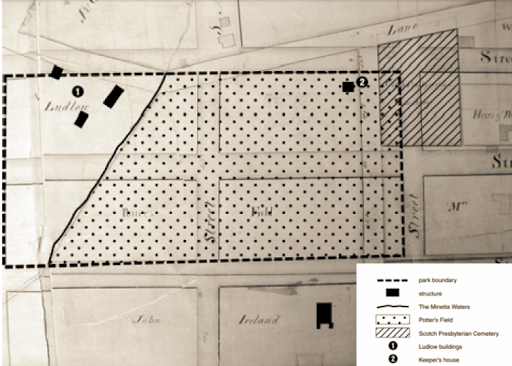

By 1797 the growing city was in desperate need of space to bury the indigent and infected. NYC was in the midst of a yellow fever outbreak that would ravage the population, hitting epidemic proportions three separate times in 1795, 1799, and 1803. With its distance from the city center, the land we now call Washington Square Park provided the perfect place. The land to the east of Minetta, which created a natural western border, was in dispute and the city purchased it easily, and the City’s second Potter’s Field was built. From 1797 until 1825, approximately 20,000 bodies were interred there. During these years a wooden fence was added, and a Keeper’s House was built for the individual whose job it was to manage the field. Eventually culverts redirected Minetta Creek underground. The land began to slowly take its now well-known shape, and by 1827 it has the same borders we know today.

It’s at this point in history that the land not only has a recognizable shape, but also its familiar use. When the Potter’s Field closed in 1825, the city purchased additional land west of Minetta Creek completing the rectangular parcel that is now Washington Square Park. The wooden fence, and the bodies, remained in place while Minetta was further redirected, and in 1826 the Washington Parade Ground opened. While there wasn’t much in the way of landscaping ーno ornamental plantings or picturesque pathwaysー it only took a year before it was considered a park by residents.

It doesn’t take much longer for the city’s wealthiest to begin flocking to the area and begin influencing the neighborhood’s design. In the 1830’s Washington Square North was built, and the first NYU building was completed by 1834. It’s around this time that diagonal gravel footpaths were added to the square, beginning the true transformation into a public Park. By 1848 we see the first effort to truly shape the space to the needs of the residents. A gardener by the name of William Curr created a new, and very formal, design plan for the space. Angular grass plots were formed by the placement of new diagonal paths. A wrought iron fence replaced the original wooden one, and a year later gas lighting was added.

Just a few years after the new pathways, the Park gets its first familiar landmark. In 1852 the original fountain is installed. This isn’t the fountain that splashes happily in the Park today. The first fountain was a behemoth, 100 feet in diameter, and it served a dual purpose: increasing the sense of “sheer tranquility and unstructured activity” called for by the popular “Pleasure Ground” movement; and showcasing the success of the recently constructed Croton Aqueduct.

By 1870 the NYC Common Council began to consider the parade ground a Park, finally catching up to the neighborhood perspective. By 1878 the New York State Legislature passed a law that named the land a public park in perpetuity. Now “officially” a park, Washington Square begins to see some more deliberate changes take place, intended to shape the space to better fit the needs of the community around it. A carriage drive was created and in 1872 the massive fountain was replaced with a smaller model, designed by Jacob Wrey Mould and appropriated from Central Park. Three buildings were also added: a music stand , a Police Shelter and a Woman’s Cottage.

Between 1888 and 1920 the Park is graced with its iconic monuments. First to the scene is Giuseppe Garibaldi, the “Uniter of Italy.” It is dedicated and placed in the Park in 1888, and no one is really sure why. It may have to do with the Italian community that lived south of the Park and donated small sums for its erection, but it is just as likely that Garibaldi found a home in WSP because that’s where there was space for him. Next came Alexander Lyman Holley, for equally obscure reasons. Lyman was responsible for adapting the Bessemer steel-making process to US production needs; not exactly a natural fit for the Park. Nevertheless, he was dedicated and placed in 1890.

The first monument installed in Washington Square Park that is truly FOR the Park, is also the one most of us know best: the Arch. Built from 1890-1892, the Arch was a tribute to the first President of the United States, George Washington. It is actually the second Arch built, inspired by a temporary structure that was built in 1889 to ensure that the parade celebrating the Centennial of Washington’s Inauguration would pass by the Park bearing his name. It was such a hit that Stanford White was commissioned to design a permanent version in marble. Fun fact: while the Arch was completed in 1892 and dedicated in 1895, the statues of Washington weren’t completed or installed until 1916 (east pedestal) and 1918 (west pedestal) due to delayed funding.

Last but not least, the WWI Memorial Flagpole was dedicated and placed in the Park in 1920, honoring the neighborhood heroes who died in the war. Although you might not know it at first glance, the Arch and the flagpole have some important things in common. Like the Arch, the flagpole was created specifically for Washington Square Park, a monument for the community. It was also designed by the architecture firm of McKim Mead and White, co-led by none other than Arch architect, Stanford White.

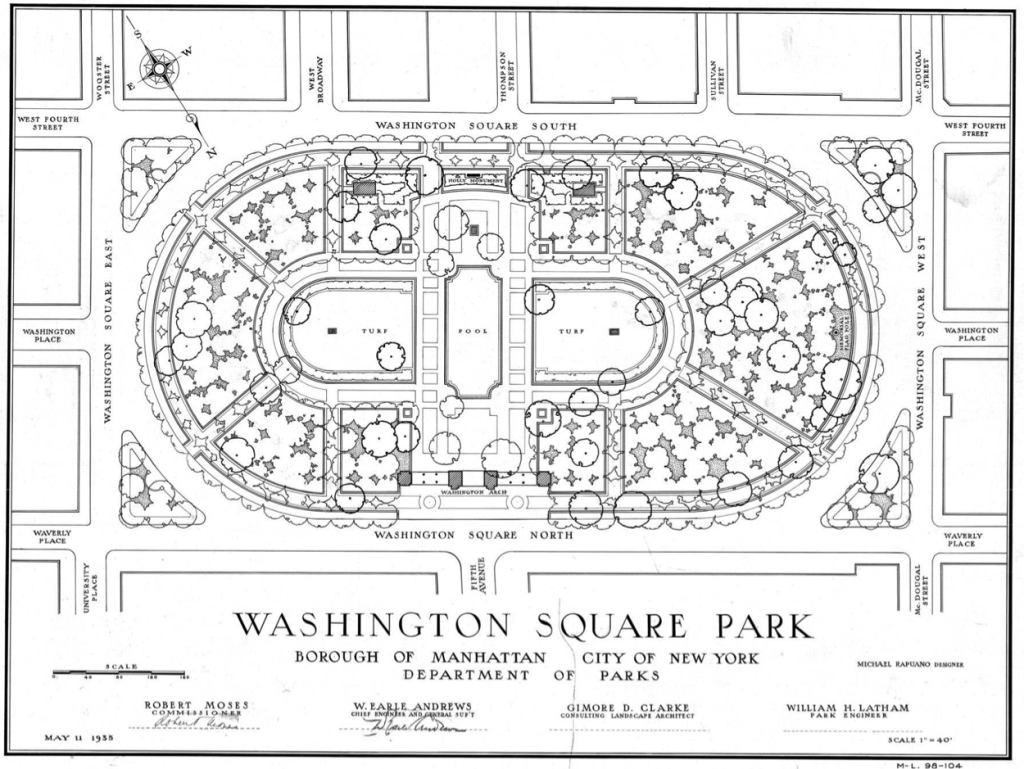

Beginning in 1934, public parks are unified under a single city agency, NYC Parks, and Robert Moses takes the stage. When you think of Moses and Washington Square Park, what probably comes to mind first is his plans to build a highway through the Park. Thanks to outcry from the community, which was quite clear on how it wanted the space to be used, those attempts were unsuccessful. So unsuccessful in fact, that by 1959 traffic through the Park was stopped entirely. But we do have Moses to thank for a few essential Park elements: he added four steps down into the Fountain, converting it from an ornamental piece into a wading pool; he added the beloved chess tables in the SW corner of the Park; and he built a new comfort station. These changes further developed the Park as a space for people, with their entertainment and comfort the priority.

The landscape of WSP remained mostly unchanged for the next few decades, and by the1960s it was in need of sprucing up. Led by Villager Robert Nichols, the community demanded an overhaul of the Park to repair the declining landscape and modify the Park now that traffic was no longer allowed. By 1969 the renovation was underway, creating a sunken space around the fountain and adding low concrete walls.

Generations of New Yorkers listened to music in the sunken fountain and hung out at teen plaza. But by the early 2000s, the Park was in disrepair and in need of 21st century design ideals. . In 2007 the most recent renovation began, adding 20% more green space The Fountain was raised to grade, and centered on the Arch. p and The entire Park was made ADA accessible and priority was given to carving out unique spaces in the Park appropriate for multiple types of uses. The design enhances everything that we love about the culture of Washington Square Park. There are places to play and repose, to connect with nature and history, and to engage in activities from Yoga to tango to nighttime movie screenings. Washington Square Park is built for its community. Quirky and unique and endlessly beautiful.

If you want even more info on the past and present of Washington Square Park, enjoy this recording of a lecture given by WSPC Community Development Director in partnership with Village Preservation from 7/29/20.