The Original Parkies

When you’re standing in the middle of Washington Square Park — one of the most iconic spots in the world — it’s hard to picture it as anything but a public park space. But long before millions of people began traipsing along the curving pathways and picnicking on the carefully tended lawns, this space was wild. No, not the wild of 1980s NYC, but the wild of a thriving marshland teeming with plant and animal life that was home to a community of people called the Lenape.

As Turkey Day approaches, we often find ourselves telling the story of the first Thanksgiving, and the Native Americans that cheerfully celebrated alongside their pilgrim friends. It’s a familiar narrative, taught to us with sing-song voices by pleasant elementary school teachers; Squanto and the pilgrims, the corn and the games. But these stories are fabrications, watered down in an attempt to gloss over a harsher reality that doesn’t fit so well with pumpkin pie.Instead of another stale rendition of the First Thanksgiving, we’d like to take a moment to explore the history of the Lenape.

Manhattanites might not realize that the name of this borough is derived from the Lenape name for the island, Mannahatta, which means the land of many hills. It would be nearly unrecognizable to us today. Where Times Square now sits was a lush forest with a beaver pond. The Jacob K. Javits Federal Building, at Foley Square, was the site of an ancient mound of oyster middens. And Washington Square Park was part of a larger settlement known by the name Sappokanican, which roughly translates to the “Land of Tobacco growth.” Here the Lenape would have gathered to trade, play games and music, and gather with the community, uses not so different from the ones we see in the Park today.

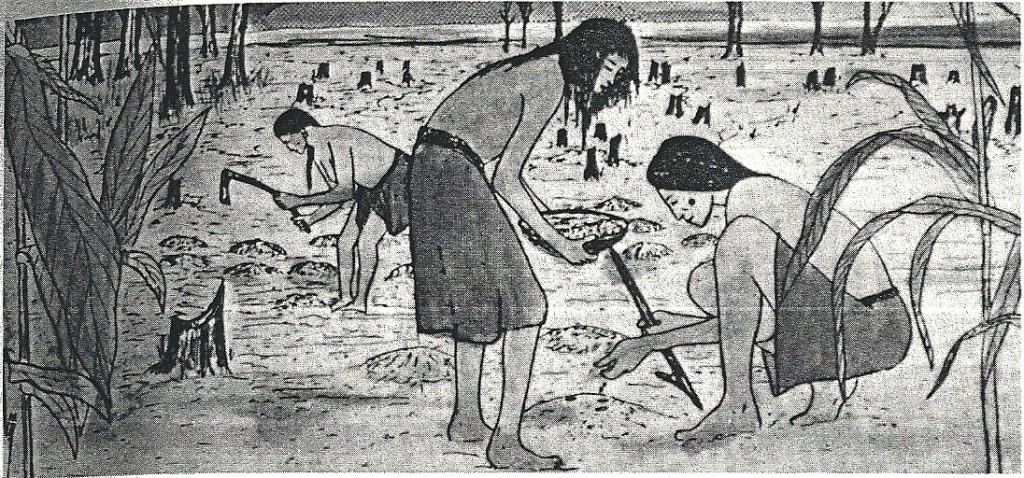

The Lenape spent their days migrating between a number of similar seasonal settlements across what is now Manhattan, Westchester, Northern New Jersey, and Western Long Island. Farming was an important part of Lenape life, although they did not conceive of private land ownership in the way we do today. The land didn’t belong to an individual, but instead to families within the clan collectively while it was inhabited, until resources and seasons dictated they move on to a new site. And the land that Washington Square Park now inhabits was particularly lush. Starting west and running south of where the Arch now stands flowed one of the largest natural watercourses in Manhattan, Minetta Creek. Minetta may have come from the word Manette meaning Devil’s Water. Although the creek was buried in the 19th century, it still resonates as part of Greenwich Village history. Fun fact: Minetta Street was built following the curvature of the creek’s original path.

Often the Lenape are confused for a single tribe, but the reality is much more complex. The Lenape people were comprised of smaller tribes who spoke similar languages and shared familial ties, but were spread across a vast swath of the Northeastern Woodlands, what we would today call Canada, New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania along the Delaware River watershed, New York City, western Long Island, and the Lower Hudson Valley. They didn’t even all speak the same language. Some Lenape spoke Unami while others spoke Munsee. Although all Lenape belonged to the same larger group, a Lenape citizen would have identified first with immediate family, clan and village, then neighboring villages, and finally would find kinship with more distant communities through their shared language. But their identity as “Lenape” was not paramount.

As is the story with all Native American tribes, the Lenape way of life was irrevocably altered by the arrival of European settlers. When the Dutch first arrived in Lower Manhattan in 1624, relations were peaceful. But the peace was not to last. In a now infamous—and quite dubious—story, the Lenape “sold” Manhattan to Peter Minuit, Director of the settlement, for 60 guilders, or about $24 at the time. This tale is frequently held up as an example of European cleverness, or Native American naivete, but remember: the Lenape didn’t view land as something that could be owned the way Europeans did. What Minuit believed was a purchase, was likely viewed by the Lenape as an exchange to allow the Dutch to share the land, treating it with the same reverence as the Lenape themselves did.

While there is no historical evidence to prove that the meeting between the Lenape and Peter Minuit ever took place (it appears there was no secretary on hand to take minutes), we do know that “sale” or no, the Dutch claimed ownership of Mannahatta. Unsurprisingly, that didn’t go over well with the Lenape, and violent conflicts with the Dutch increased as settlers laid claim to the land and the Lenape struggled to protect their home. And if battling against more modernly armed forces wasn’t enough, the Lenape died in droves from disease brought to the land by settlers. Even the English ascension to power in 1664 offered no respite for the Lenape. By the early 1700s, the few hundred who managed to survive the European invasion were forced to leave Manhattan.

While they may be on our minds more during this time of year, it isn’t only at Thanksgiving that we should acknowledge the first stewards of the beautiful land we now call Washington Square Park. While Minetta may now be buried, and the marshland has been tamed, the long history of this place cannot be erased or forgotten. And the Lenape are not gone, although many now reside outside of New York State. In fact, in 2019 a number of tribes returned to Manhattan for the first Pow Wow in over 300 years. So next time you’re in the Park, take a moment to stop and think about the original Parkies who loved this space as much as we do, and acknowledge the less than beautiful history that brought us to today.