Washington SCARE Park

The days are getting shorter, the air is getting cooler, and the leaves are beginning to change. The Halloween season is upon us; a time to give ourselves the chills by telling spooky stories in the dark. In the spirit of the season, we’re sharing (and debunking) some Washington Scare Park stories that may be more myth than history.

A Public Burial Ground

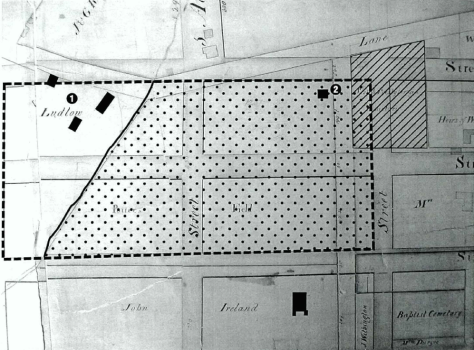

Do you ever think about what’s beneath your feet as you stroll around Washington Square Park? Of all the chilling tales that linger about this place, one of the most unnerving is also the truth. Before the land of Washington Square was a public park, it was a potter’s field: a public burial place where poor and indigent people were interned. It has been estimated that there are 20,000 bodies in the ground beneath our feet, many of them victims of yellow fever. There were multiple epidemics of the terrible disease: 1797 , 1798, 1801, and 1803. During this period, the land that became Washington Square Park was still considered a rural part of the city. Combine the remote location with the proximity of numerous churches with their own cemeteries, and it was the perfect location for such a grim necessity.

An Execution Ground

While it is true that Washington Square Park was once a potter’s field, that fact has given rise to many macabre and untrue rumors. One of them is that the Square served double duty as an execution ground. The story goes that soon after the burials started, the city sheriff erected a public gallows near where the fountain currently sits and began performing executions and burying the bodies in the field. With the potter’s field solidly established, and prison on the Hudson River less than a mile away to supply necks for the gallows, it’s easy to understand why this story may have started. However, according to City records and newspapers of the day there is only one documented hanging that took place in the Potter’s Field: that of Rose Butler.

Rose was a young domestic slave who was only 19 years old when she was convicted of arson for attempting to burn down her master’s home while they slept. Although there was minimal damage and no one was harmed, Rose was still sentenced to hang.

This terrible incident took place in 1819 during New York’s complex period of gradual emancipation, when blacks might be free, indentured, or remain in slavery based on their age. Slavery in New York did not come to a definitive end until 1827, the year Washington Square opened as a Park.

The “Hangman’s” Elm

Another story likely born from the Park’s history as a potter’s field is the myth of the Hangman’s Elm. By the northwest entrance of Washington Square Park stands one of the oldest trees in Manhattan. This beautiful English Elm has a dark–and unearned history ascribed to it.

The legends vary slightly, but the stories all make the same general claim: that the tree was used for executions by hanging. In one variation, the story goes that traitors were hung from it during the Revolutionary War. Another version says Marquis de Lafayette himself watched 20 highwaymen swing from its branches. However, there is no hard evidence to back up any of these tales. In fact, one piece of historical evidence actually helps to disprove the narrative. For most of its existence the English Elm stood on private land and not in the potter’s field. One thing that can’t be denied, this tree has witnessed much in its approximately 350 years.

Roosevelt’s Dog

Unlike our other spooky stories that seem to have been inspired by a small kernel of truth, this one is pure wild imagination. Washington Square Park is haunted. Not by the souls of the 20,000 buried beneath our feet. Not by Rose Butler, the slave girl wrongly put to death. But by a little black dog named Fala.

From 1942 to 1949, Eleanor Roosevelt lived at 29 Washington Square right on the corner of the Park. And Fala was her dog, well, her husband’s to be precise. Up until his death in 1945, President Roosevelt was a doting owner to the little Scottish terrier. The dog would have gone on walks in the Park while visiting Eleanor before 1945, and in the years he lived with her after his master’s passing. It is said that on a quiet night you can still see the little dog wandering through the Park, sad and lonely, looking for his beloved President.